Fred Lorenzen

Chuck Arrobio

Bobby Hull

George “Holt” Taylor

Michael Root

Conrad Dobler

Jacob Sinclair

Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide that may be triggering to some readers.

Jacob “Jake” Dean Sinclair was born at 4:18am on October 23, 2006, in Stafford, VA. Funnily enough, he wasn’t yet known as Jake at the time. I woke up that morning at 3:00 a.m. and we barely made it to the hospital, still undecided about a name. My husband Chris’ grandfather had decided upon himself he would call our child Jake, no matter what anyone else said. So, we landed on the name Jacob Dean, after both of our grandfathers. To teachers, friends, and strangers he was Jacob but to family, he was Jake.

Jake was the baby of the family, following our first son Tyler (born in 2000) and our daughter Autumn (born in 2004). He loved both his siblings immensely. I still remember the day Jake was born, Autumn walked into the room demanding we give her the baby. She adored him as if he was a real-life doll, picking out some of his clothes even into his teens which he wore without hesitation.

From a young age, Jake was caring, sweet, bright, respectful, and a wonderful friend to all. He had a big heart and loved making everyone laugh.

And of course, Jake’s hair. He’d probably tell you his curly hair was his best quality.

Growing up, Jake was your typical teenager. He enjoyed going to games at school, to the movies or concerts with friends, and playing his Xbox. Jake especially liked tagging along with his sister wherever she went – on Target runs, to Goodwill, out for ice cream, and dog sitting. As with anyone his age, he was constantly on YouTube and TikTok, showing us videos he thought were funny. And at family gatherings, Jake loved talking with uncles and cousins about his hometown team, the Washington Commanders.

If Jake wasn’t watching sports, he was playing them. He wanted to play football when he was still in preschool but didn’t officially start until age eight, as soon as he was old enough for parks & rec. Jake then played through his freshman year of high school but was recruited to the lacrosse team and made the switch. He also wrestled for a few years in middle school, winning most if not all his matches.

In football, Jake switched between offense and defense and there were games where it seemed like he never left the field. He thrived as a defensive end, always breaking through the O-line and sacking the quarterback. Because of his prowess, there would always be two or three guys on him every play.

Jake’s first diagnosed concussion occurred in April 2023 during a lacrosse game, when he ran headfirst into another player. He was evaluated by the athletic trainer who sent an email to me and his teachers a day later, informing us Jake had suffered a concussion. When I told him I was making a doctor’s appointment to get checked out, he only complained of a headache and light sensitivity otherwise he felt better. But after Jake passed away, I saw from old posts on his phone he only said that so he could get cleared to keep playing.

A second concussion occurred a few months later in August, after Jake flipped a golf cart at work. He had a visible mark on his head and complained of a headache. The physician said Jake had a “mild concussion” and to simply avoid light and rest. When I again reviewed text messages, I realized he was asking for headache medicine multiple times a week, sometimes more than once. He also mentioned having insomnia in social posts. On the day Jake passed, he told his girlfriend he almost fell down the stairs from dizziness.

We only found out these details after Jake’s passing once we had access to his phone. We had no idea how much he was struggling as he’d blocked the entire family from his social media accounts. I don’t think he knew these were possible concussion symptoms or understood what was going on in his head.

After Jake’s concussions, we noticed changes in his behavior, including impulsivity, aggression, lethargy, and substance abuse. Looking back now, it became so extreme we should have suspected something more than just a troubled teenager going through puberty. We also thought some of his behavior stemmed from the few years of isolated virtual learning due to COVID.

As a parent, I didn’t know what to do and felt like I was failing him. I’m sure there are many other parents who feel the same way about their kids. At the time I didn’t know these symptoms could stem from a concussion, so it wasn’t even on my radar. I’d catch him smoking marijuana and see Fs on his report cards. When I tried to talk to him, he would go off on me, saying what a bad parent I was and how I ruined our relationship over a little weed, which he said helped him relax.

In the last year of Jake’s life, our relationship was strained, and it affected the entire household. You can only try to ground someone so much, but he would still sneak out and do whatever he wanted. Especially once school started, I think he was able to smoke all day without any consequence. We barely recognized this version of Jake. In my mind, I just hoped this was a phase and we could get through it.

On the day Jake passed away, it was snowing so there was no school. It started off like a typical day; Jake had slept in then after lunch we spent time making plans for our annual trip to the Outer Banks. He also mentioned wanting to sign up for the junior fire academy during his senior year. I agreed, if he turned in all his missing homework assignments which had started piling up.

While my husband and I were making dinner and cleaning up around the house, Jake asked if he could go to a friend’s house. I told him no since the roads were bad and he hadn’t yet improved his grades. Jake snapped and started yelling at me. I told him I wasn’t going to argue, and he needed to calm down. He took his food and went to his room. Our daughter Autumn went to check on him after dinner but found his door locked. When we got inside, Jake was unresponsive.

That evening and the blur of days after, we tried to process what had led to Jake’s death. My husband mentioned the concussions and if they might have played a part. Following the funeral, my stepmother sent me an article featuring Wyatt Bramwell, saying his story sounded just like Jake’s.

Reading Wyatt’s story, I was astounded by the similarities. While my husband had heard of CTE before, this was the first I learned of the disease or any long-term effects of concussions. And both of us didn’t know it could affect someone so young until the article. I then went through other Legacy Stories on the CLF website – Austin Trenum’s was another which read just like Jake’s. One minute, everything was fine and he was making plans for the future. The next, we had an argument and then he was gone.

We had no idea the connection between concussions and suicide risk and don’t believe Jake did either. Since his passing we’ve learned his struggles were not at all uncommon for someone healing from a brain injury. Multiple research studies have shown a link between concussion and suicide risk, with one study finding those who suffer a concussion are twice as likely to take their own lives. That is such an important statistic for all parents to understand, especially those who have children who play contact sports!

I got in touch with the UNITE Brain Bank and due to the circumstances of Jake’s death, his brain was unable to be studied. Though there may be no official diagnosis, I’m sharing Jake’s story because I want other families to know what to look out for when their child has a concussion. I also want the entire athletic community, from trainers, coaches, and medical personnel, to know they need to better educate players and families/caregivers about Post-Concussion Syndrome and suspected CTE. And to those currently suffering, I want you to know there are resources out there to help you.

Jake was so loved by so many people. No one had any idea he was depressed or suicidal. I just wish Jake had known he was that loved while he was still here.

_____________________________

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

Mabel Gonzalez

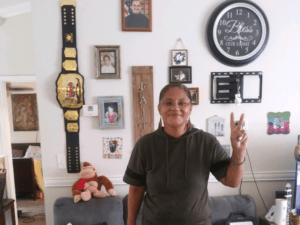

Merriam-Webster offers numerous definitions for the word “mother,” reflecting the diverse ways it can be understood. Yet, none fully capture the essence of Mabel Gonzalez.

My mother embodied them all. She was a protector, nurturer, provider, advocate, teacher, and mentor. To others, she was a warrior, soldier, angel, sinner, and saint, caught in the eternal struggle for kindness, ethics, and morality in a world that often loses its way.

Mabel was an anomaly, someone who should not have existed. A descendant of an oppressed people spanning over eight centuries, she carried the spirit and soul of liberation, survival, and peace with every breath and through every moment she graced this earth.

She was the youngest daughter brought into a world which deemed women inferior – and women of color even more so. My mother embodied both identities, and her profound double consciousness manifested in her professional and personal pursuits, fighting tirelessly to be recognized in a fractured society that viewed women like her as shadows they couldn’t erase.

Mabel was a trailblazer who shattered glass ceilings and broke through walls simply to survive. She refused to perpetuate the intergenerational trauma of being a silenced woman, living in the shadow of a man. As a young adult, she rebelled against gender norms, racial stereotypes, and society’s expectations by becoming a voice for the voiceless – a mother who chose to speak alongside her children rather than from behind them.

Her conviction shone through in the way she parented her eldest son Luis, breaking cycles of disconnection and raising him with a revolutionary spirit of inclusion. Without formal knowledge of child development, she intuitively nurtured her children in alignment with the latest science, relying solely on her boundless love and instincts.

This enlightened approach to child rearing continued with her two other sons, who were seen and heard in ways their parents never were. Her resilience and awareness propelled Mabel to become a social pioneer, culminating in her role as the first-ever Parent Coordinator for New York City public schools under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

But Mabel’s achievements did not end with her career. She dreamed of retiring in a place where she could savor the peace and dignity of true autonomy, having left an indelible mark on her family and community.

Mabel endured the unthinkable tragedy of losing her youngest son in an accident, an irreplaceable love lost forever. Yet, even in the face of this devastation, she became a grandmother while carrying the weight of her grief with grace and courage. No one I’ve ever known could weather the storm as she did, offering steadfast love and strength to those of us adrift.

My mother’s passion for women’s liberation and autonomy defined her life. She hoped her sacrifices would pave the way for a world where future generations of women would not face the same struggles she endured.

Some might wonder how this extraordinary woman connects to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. Mabel’s fight for a better life was constantly met with fierce resistance. Her battles left her a wounded healer—a testament to the urgency of recognizing and addressing the trauma endured by the human brain.

Head trauma knows no boundaries of race, class, or gender. Women often face this silent epidemic because of gender-based and intimate partner violence—realities as perilous as any sport. Contact sport athletes may accept the risks of their profession, but women should never have to accept risks to their safety and brain health simply for existing independently.

Mabel’s legacy serves as a clarion call to athletes and society alike. She wanted the world to recognize the dangerous “sport” of women and civilians enduring brain trauma, often while sacrificing themselves for their loved ones in unimaginable moments. Her life and death stand as a tribute to families forced to leave the sidelines and step in when courage is required.

My mother lived by the inspiring words of the late Senator Robert Kennedy, for she too “dreamed things that never were and said why not.”

I hope her Legacy continues to inspire future physicians and clinicians to bring awareness to communities that lack the resources to blow the whistle on gender-based violence. In spirit, she remains steadfast in her mission to uplift future generations of women, advocating for a world where being a woman is defined by love and compassion, not violence.

________________________

If you or a loved one are in a domestic or family violence situation, please contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline here to speak with trained expert advocates who can offer support, education, and crisis intervention information. It is free, confidential, and available 24/7/365.

A Pro Skateboarder’s Recovery from Repeated TBIs

My name is Alex Willms, and I’m a 26-year-old skateboarder from San Diego. I’ve sustained more than 20 concussions in my life, which have affected me in different ways. I still struggle with my recovery, but I’ve decided to share my experience because I know there are a lot of other people out there suffering.

For me, each concussion led to the next.

My first TBI was in 2004, when I was 6 years old. The impact was on my forehead, and I lost consciousness for about four hours. I was discharged from the ER the next day with instructions to rest and was told everything would be fine in 1-2 weeks.

As a child, I dismissed the event as soon as the pain subsided, which took about a week. The ongoing effects were much more subtle. There were many other difficulties in my life that I didn’t connect to this early TBI until two decades later.

After the brain injury, my left eye began shifting inward and has been like that ever since. I also experienced difficulties with speaking and social withdrawal. The worst were the symptoms of executive dysfunction: impulsivity, emotional reactivity, difficulty making decisions, and more.

But the most frightening thing I have learned is how a history of previous concussions, especially in childhood, can increase the risk of developing concussions in the future.

Seven years after my initial injury, I started having severe migraines. They’d last up to 11 hours and could take two weeks to recover from. I lived in fear of these migraines my whole adolescent life, so I wore a helmet while skating for a long time.

Skateboarding was always my first love. My neurological issues bled into all aspects of my life, including what I care about most.

Most of introductory skateboarding is learning how to fall. This includes adopting habits that help avoid whiplash and blows to the head. Without realizing it, I learned not to concern myself with these strategies, thinking a helmet would protect me. I picked up some additional concussions in my teenage years — with a helmet on — because of this.

Around 2015, at age 17, the migraines dissipated. Thinking they were gone for good, I stopped wearing a helmet with hopes to pursue a career in professional skateboarding. However, my patterns of letting my head hit the ground didn’t disappear.

In 2018, I sustained my second life-changing TBI. While I have no memory of the day, I’ve seen footage and heard from friends that my left temple struck the ground from a high impact, causing a grand mal seizure. The paramedics took me to the hospital, where I was put into a coma for about 15 hours. I woke up with no conception of reality, but things slowly started to return to normal. I got back on my skateboard one month later, a dangerously short amount of time.

After this TBI, my mental reality gradually collapsed. I couldn’t calm down around other people. Speaking felt impossible. When I tried to talk, the words that came out always felt like the wrong ones. I became withdrawn.

My personality changed. In the months and years that followed, my communication and relationships deteriorated. It was hard watching my friends get confused or angry with me. But what hurt the most was seeing them come to accept I was now different, before I was able to do so myself.

Concussions play dirty, in that your specific struggles before the impact can be the first to worsen after it. My growing instability blended so seamlessly with my insecurities before the accident. My newly heightened emotions felt more natural than ever; I didn’t realize they were stemming from cognitive impairments.

I felt physically unaffected, and in my fractured mind, that meant I could skate —I needed to skate. Skateboarding can be very healing when it comes to emotionally traumatic events.

Two months after the 2018 TBI, I suffered a concussion that left me delirious, briefly unsure of what month it was, and bleeding from the face and chin. For the next few years, the frequency of concussive incidents increased drastically.

I believe the 2018 TBI served as the root of this spike, as I never fully recovered before sustaining additional injuries. Continuing to skate aggressively during this time likely fueled my struggles, but I didn’t want to admit it to myself. I wanted to keep skateboarding in an impulsive, unbalanced way. It was all I had to take me away from what was going on inside my mind.

In April 2023, I sustained another TBI after my right temple struck the side of a stair with a lot of force. This one finally pushed me over the edge, leaving me with disabling physical symptoms. Ultimately, I ended up pushing myself too hard too soon after the impact.

I developed postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) in addition to persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS). POTS is a form of dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. My worst symptoms are shortness of breath, chest pains, chronic fatigue, presyncope, insomnia, and gut pain. In addition to this, I was suffering from the effects of PPCS, which included headaches, eye strain, photophobia, and more.

The first few months were devastating as I transitioned into a disabled lifestyle. It was heartbreaking not being able to skateboard anymore. I couldn’t exercise without nearly fainting. I never truly understood chronic pain until this injury. As the months went by and my ability to walk, talk, and think seemed to be growing worse, I began having panic attacks, frightened by the uncertainty of whether I was going to live through this or not.

After spending most of my time in a dark room with closed windows, I also tested positive for mold poisoning, which only exacerbated my concussion symptoms. Since moving to a cleaner environment, my recovery has accelerated.

It’s been 21 months since my 2023 TBI, and a lot of my symptoms have improved. I’m learning to stop pushing through the pain. While I still experience chronic pain in the evenings, my quality of life has improved a great deal. I’m walking 5-8 miles daily, writing a lot, and growing closer to my best friends.

What’s interesting is how such a destructive injury tends to course correct many unhealthy habits. If you stare at screens for too long, the sensitivity to light will keep you off your phone and in the present. If you eat too much junk food or drink too much alcohol, the resulting pain will push you to improve your diet. Using pain as a cue like this makes the whole process a lot more purposeful. It’s how you learn.

While I still run into setbacks, I’ve learned a lot of adaptive strategies that have helped in my recovery. It’s normal to run into these complications. With each one, you learn a little bit more about how to check yourself. After a flare, it seems very convincing that all your progress is lost. It is not.

Doors of opportunity may close after a brain injury. There might be some you can reopen in time. In exchange for the lost doors, new ones will open in their place.

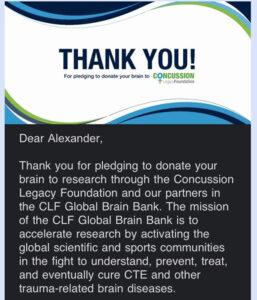

I’ve pledged my brain to the UNITE Brain Bank so my loved ones will someday know if I had CTE. The possibility of CTE is a painful one that surfaces often. I try to cope by staying disciplined through living healthy and staying focused. If this is something you struggle with, I find it helpful to remember that being a living example of what this process is like — as frightening as it may be — could help others understand, prevent, and survive this disease in the future.

Some practices I’ve found most effective are meditation, diaphragmatic breathing, physical therapy, acupuncture, ocular exercises, diet and supplementation, hydration with electrolytes, cold water exposure, and listening to audiobooks.

To cope with PPCS, finding a specialized concussion clinic is essential. The CLF HelpLine can help you find one, as they did for me.

I’ve also found it very helpful to get in contact with others who have experienced TBI. CLF has a peer support program you can learn more about here.

There are people out there who understand brain trauma and its physical and emotional ramifications. It’s crucial to open up about your situation to people you trust. Seeking support from caring friends and family can change the trajectory of your recovery.

Faith is at the heart of recovery. It is the bottom of the pyramid. The more you instill hope and excitement for your future, the easier your symptoms will be to manage. Paying attention to potential lessons from the present struggle directs you towards a better path. After enough practice at this, making healthy, impactful decisions becomes a system that runs itself.