Chris Simon

Gabriella Sipe

Denny Oechsner

Concussions: Navigating a Decade of Brain Trauma with My Son

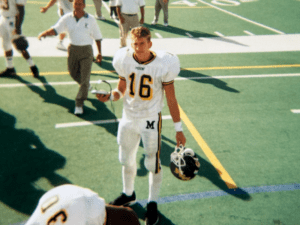

My son Ryan began playing youth tackle football at the age of eight and continued every year through high school. For four years, he was the celebrated dual quarterback and running back for the Mount Saint Michael varsity football team in New York City.

There is no way to document the number of concussions Ryan sustained, as there were simply too many to count. Players were encouraged to “man up” and get back out there no matter how badly they were hurt. All I know is he suffered a decade of brain trauma, from when he started playing up until the age of 18.

In the book Concussions and our Kids by Dr. Robert Cantu, the doctor explains that helmets offer no protection to a child, since their brain shakes inside the skull with every hit, disturbing the connections inside of a growing brain.

As young parents, we were under the impression our children were protected by their padding and helmets. It appeared the coaches had faith in the equipment as well, since they were enthusiastic in telling their players to make aggressive tackles.

Ryan began showing symptoms of aggressive behavior during his senior year of high school. He was argumentative and excitable, not like himself at all. Then in March of 2004, Ryan suffered a breakdown in his college dorm room. The next six years were a blur of frightening hospitalizations, doctors’ visits, medication trials, and despair for our entire family.

Our lives were consumed with finding the right treatment for Ryan. It turned our household upside down and is something from which we haven’t yet recovered. In 2010, Ryan admitted himself to Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City. Doctors there were concerned since many of his symptoms were related to frontal lobe damage. Ryan was transferred to a traumatic brain injury (TBI) program.

That same year, I reached out to our local Senator and Assemblyman with Ryan’s story. I also traveled to Albany with Assemblyman Michael Benedetto of the Bronx to speak about youth tackle football and its risks to a young child’s developing brain, hoping to spark interest in a bill to ban tackle football for children under 14 years of age.

In 2013, I contacted and met with Harry Carson, the celebrated Hall of Fame captain of the NY Giants. He has been an inspiration and mentor to Ryan. I joined Mr. Carson on a panel at NYU Langone Medical Center where we discussed the dangers of concussions, football, and the devastating symptoms connected with repetitive head impacts.

I continued doing my own research and discovered the Concussion Legacy Foundation in 2023. With the help of their HelpLine, we were able to find a good medical professional who prescribed a combination of medications along with vitamins and talk therapy. We also sought out and discussed our story with other parents who were struggling. Having a support group was and is such a crucial part of the healing process.

With treatment and time, Ryan began to show signs of improvement. Through New York State’s TBI Waiver program, our son was fortunate enough to meet a life skills coach, who encouraged him to exercise and helped him create inspirational videos. These served as therapeutic tools which gave Ryan the confidence to discuss his journey publicly. In one exceptional video, the coach brought Ryan to visit his high school coaches and talk about his experience.

These all proved to be a lifesaver for Ryan, who is now 39 years old and doing much better.

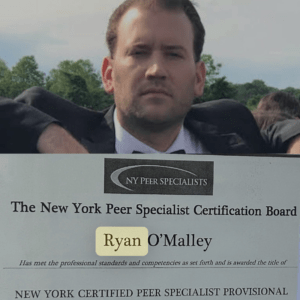

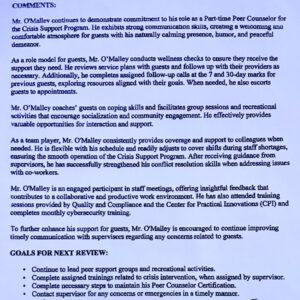

We know Ryan is one of the lucky ones. He lives with us and has the support of extended family, friends, and mentors. He exercises almost daily, including playing sports like basketball and golf, and loves to create rap songs as a hobby. He earned his certification from the Academy of Peer Services and has been working as a Peer Counselor with the ACMH Organization in Manhattan for almost three years. He has true empathy for the residents and is often asked to represent his division at staff meetings.

Ryan agrees with us that parents should think twice about tackle football for young children. He believes his story could be an eye-opener for parents who believe, as we did, that their children are being protected by their helmets. Even though coaches are more aware these days and practice safer techniques, parents need to know all the facts. We are strong advocates for CLF’s Flag Football Under 14 program and encourage all parents to understand the risks when considering enrolling their children in youth tackle sports.

Alexandra “Owl” Hinks

Christoph Trappe

Nick McCracken

John Tudor

Early life and football career

All John Tudor ever truly wanted was to play professional football. From a young age, kicking a ball wasn’t just a pastime—it was everything. Through sheer hard work and determination, he turned that dream into reality.

John began his journey with local teams before playing for Ilkeston Town, his hometown club. In 1964, he was recommended to Coventry City, where his professional career began. He quickly rose through the ranks, moving from the B team to the A team reserves and eventually fulfilling his dream of playing for the first team. Between 1964 and 1968, he made 63 appearances and scored 28 goals.

In 1968, John transferred to Sheffield United, where he earned the nickname “King Tudor.” Known for his formidable heading ability, he netted 32 goals in 64 appearances.

John’s most successful years came at Newcastle United, where he played from 1971 to 1977. Beloved for his tireless work ethic and humble nature, he formed a legendary partnership with Malcolm Macdonald. Dubbed “the deadly duo,” they thrilled fans for years. John made 234 appearances and scored 75 goals for Newcastle, cementing his legacy.

In the 1977-78 season, John joined Stoke City, scoring twice upon his debut. Although he made 38 appearances, he found the net just three more times. He then moved to Belgium to play for Gent, but injuries brought his professional career to a close.

John returned to England, becoming player-manager at North Shields in 1979 and later played semi-professionally for Gateshead from 1980 to 1983, making 30 appearances and scoring 6 goals. After his playing days were officially over, John poured that same passion into coaching, working with various clubs and groups including CC United, Tonka United, Holy Family High School, the Minnesota Thunder, and Minnesota Youth Soccer.

Health and decline

In 2011, John began to change. He was agitated, frustrated, and forgetful—something was wrong. Initially thought to be stress or depression, he was evaluated and showed signs of cognitive decline. Over time, his memory and cognition deteriorated further. He grew weary, struggled with word-finding, and feared he might have dementia.

John suffered many concussions during his playing career, including one in 1974 when a brick was thrown through a team coach window, striking him in the forehead. An MRI revealed vascular changes and persistent head buzzing.

By 2016, doctors began to consider Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) or early Alzheimer’s. He experienced twitching muscles, fainting spells, and memory loss. Eventually, he was advised not to drive. Despite visits to three neurologists, including one from the Mayo Clinic, his condition worsened. John needed 24/7 care and could no longer live safely at home.

Short-term memory faded, then long-term memory. Words disappeared. Even using the bathroom alone became impossible. Everything was a challenge. In February 2024, John entered full-time care—a heartbreaking moment for our family.

Still, I cherished every visit. We’d sit together, holding hands, sipping a proper cup of British tea, and sharing Cadbury chocolate. We’d watch football and the TV show Vera, which brought him joy, as did the film The Greatest Showman. Music remained a strong emotional connection, and he especially loved emotional songs which made us both cry.

John’s health continued to decline and after fainting and falling, he was hospitalized. Some days he could walk, others he could not. He eventually became bedbound and was placed under care in July 2024. We are so thankful to everyone there who brought him comfort through music therapy, massage, and loving attention. Our son Jonathan visited often, bringing joy during those final days.

We found out about the chance to donate John’s brain through Dawn Astle, the daughter of football legend Jeff Astle, who was the first English professional footballer with a public CTE diagnosis. It gave us comfort to know John could play a part in advancing research and help future families from going through the same difficulties.

Final days

On February 9, 2025, just over a year after entering hospice care, John passed away. He was 78. He had battled courageously for over a decade.

John was loved deeply—not just by our family but by everyone who knew him. The outpouring of affection after his passing was immense. He remained humble, grounded, and kind throughout his life. He was the guy next door who just happened to be famous.

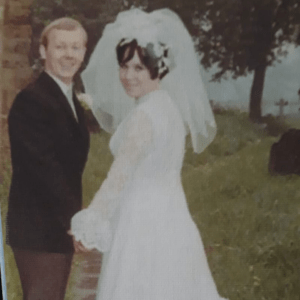

We were together for more than 60 years and would have celebrated our 56th wedding anniversary on May 24, 2025. I miss him terribly, but I’m so grateful for the life we shared.

We have two children—Shelley in the UK and Jonathan in the US, who inherited his father’s passion for soccer and now serves as the coaching director for Chaska Soccer Club. Our three granddaughters each reflect a piece of John: Brianna, who plays college soccer in South Dakota; Gracie, who lives in England; and Violet, a gifted French student. Though not all follow the game, they all know how great their granddad was.

Help for the next generation of athletes

It’s only fitting that a man who gave so much to others in life could continue helping just as many after his passing.

After speaking with Dawn Astle, we as a family made the decision to donate John’s brain for research — a vital step toward better understanding the condition that affected him. While the link between heading the ball in football and long-term brain health still requires greater clarity, we’re honored his legacy will now contribute to that progress.

John’s generosity and strength live on in the important discoveries that will come, helping to protect future generations of players while deepening our understanding of the game he loved so much. If he had the chance to live it all again, I believe he’d do it just the same.

Hallelujah, John Tudor.